My middle school years were spent in an English-medium school in India. Among our assigned literature readings was a short story by Edgar Allan Poe named "The Gold-Bug." This story introduced me to cryptography, the science of secret messages.

Every time you swipe your credit card to buy something, or log into your bank account, you're using cryptography. Modern life is built on top of certain major advances in this field since World War II, and Edgar Allan Poe's story played a role in inspiring the people who made them.

The Gold-Bug is not much of a story, as far as plot and character go. While collecting a rare beetle on a beach, a white man and his black manservant discover an old parchment paper with a message written in strange symbols, some sort of secret code.

The story spends most of its pages explaining how the man cracks the code to discover where a pirate's treasure is buried. Still, it's got enough atmosphere of mystery with a hint of the macabre, with disappearing ink, skulls nailed on trees, and a good body count, to hook a young person.

At the time, I had no idea who Edgar Allan Poe was, and how old this story was. But since coming to Boston, where he was born and where the city has a statue of him on Boylston Street, I've learned more about the tortured writer's life and his obsessions. His 215th birthday would have been last week.

It was around 1840 that Poe's fascination with logic and reasoning led him to study the encoding of information. In those days, most people thought of the art of writing secret messages as a kind of occult magic. Poe, however, ever the rationalist, dismissed such fancies. Anyone could write and break secret messages via logical reasoning.

He wrote "The Gold-Bug" as an introduction to the topic, then submitted it to a Philadelphia newspaper's writing contest and won a hundred dollars for it. The paper published it in 1843. It's probably the oldest piece of fiction to incorporate cryptography, and certainly the first to use the term.

The secret message in the story is an example of a simple substitution cipher, where each letter in a piece of text is replaced by some number or symbol. To read the message, you need a key, a table that shows which symbol stands for which letter.

These substitution ciphers can be decoded without a key by systematically applying logical reasoning and exploring different possibilities.

Assuming the message is in English, you start with a table of how frequently various letters, sequences of letters, and words appear in typical English-language text: e is the most frequent letter, followed by taoinshrdl and so on. In the story, the protagonist counts the frequencies of the symbols on the parchment and writes out an entire table: 8 is the most frequent character, semicolon is the next most frequent, then 4, and so on.

This analysis gives you a place to start. Perhaps 8 stands for e, semicolon stands for t, etc. You try these substitutions to see if the message spells out English words, and if you see mistakes, you can change them until you have figured out the key.

This kind of analysis is similar to the mathematical models needed to generate text, as I discussed in an earlier blog post about generative text models like ChatGPT. Claude Shannon, who laid the foundations of information theory after World War II, once told an interviewer that he had read The Gold-Bug as a child.

When I first read this story in middle school, I used the cipher devised by the protagonist to uncover the secret message. But the resulting message was not correct: it produced the word "fosty" instead of "forty."

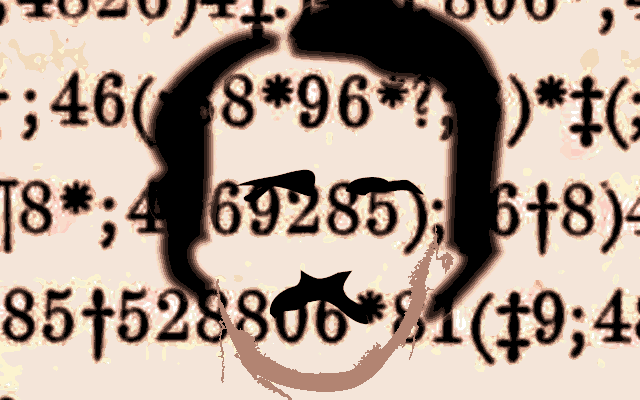

The story as published in various outlets has different mistakes in the typography of the parchment paper. I have seen at least three different versions with different mistakes.

The version in the picture above is the scan in the Gutenberg website. It has the same mistake as the one I read, producing the word "fosty" in the resulting message. But it couldn't have been Poe's fault. By the time he wrote The Gold-Bug, Poe had done a pretty thorough analysis of hundreds of messages submitted by his readers in response to his essays on cryptography in another magazine.

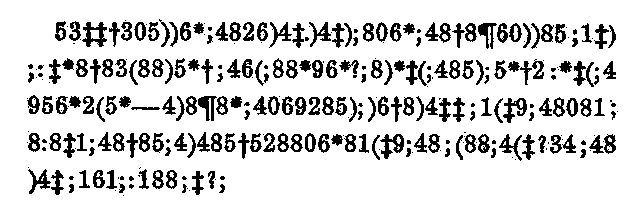

Fortunately, we now have the original version of the story painstakingly scanned and proof-read by The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore on their website. They have scanned The Gold-Bug from the original Dollar Newspaper, where it appears without any mistakes:

5 3 ‡ ‡ † 3 0 5 ) ) 6 * ; 4 8 2 6 ) 4 ‡ . ) 4 ‡ ) ; 8 0 6 * ; 4 8 † 8 ¶ 6 0 ) ) 8 5 ; 1 ‡ ( ; : ‡ * 8 † 8 3 ( 8 8 ) 5 * † ; 4 6 ( ; 8 8 * 9 6 * ? ; 8 ) * ‡ ( ; 4 8 5 ) ; 5 * † 2 : * ‡ ( ; 4 9 5 6 * 2 ( 5 * — 4 ) 8 ¶ 8 * ; 4 0 6 9 2 8 5 ) ; ) 6 † 8 ) 4 ‡ ‡ ; 1 ( ‡ 9 ; 4 8 0 8 1 ; 8 : 8 ‡ 1 ; 4 8 † 8 5 ; 4 ) 4 8 5 † 5 2 8 8 0 6 * 8 1 ( ‡ 9 ; 4 8 ; ( 8 8 ; 4 ( ‡ ? 3 4 ; 4 8 ) 4 ‡ ; 1 6 1 ; : 1 8 8 ; ‡ ? ;

Enjoy!